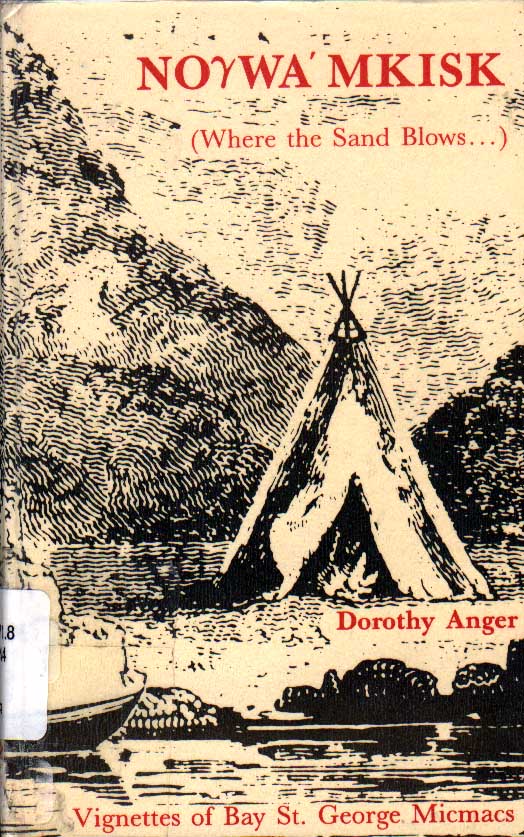

N0YWAMKISK (Where the Sand Blows...)

Vignettes of Bay St. George Micmacs

Dorothy Anger

1988 Bay St. George Regional Indian Band Council Port au Port East, Newfoundland

Copyrightฎ 1988 Bay St. George Regional Indian Band Council.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

Bay St. George Regional

Indian Band Council

P.O. Box 300

Port au Port East

Newfoundland AON 1TO

Cover Design: Ray Amiro

Text Design: Jesperson Printing Limited

Typesetting & Printing: Jesperson Printing Limited

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Anger, Dorothy C. (Dorothy Catherine), 1954-

Nofwarhkisk (Where the sand blows.. .)

ISBN 0-920502-95-4

E99.M6A53 1988 971.8'00497 C88-098630-1

Acknowledgements

The idea for this book came from the Bay St. George Regional Indian Band Council, and in particular their former Chief, Neil Lucas. He wished to see a book which told the Micmac people about their history and also showed documentary evidence of their presence in Bay St. George. Chief Lucas, along with the present Chief, Roy Gaudon, and the Band Council gave continued encouragement and help with this project. The Department of the Secretary of State provided funding for writing and publishing, and Ray Amiro of the Newfoundland and Labrador Regional Office went beyond his duty by giving time, advice and practical assistance. Edward Tbmp-kins, formerly of the Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, found material for me, arranged for the photographs, edited and gave much needed direction to the project. Chris Brookes edited, advised and helped me with the wonders of computer technology. Alex and Cedric provided their usual support, as did Gary Wilton. Staff and researchers, former and present, of the Bay St. George Band Council and the Federation of Newfoundland Indians provided materials and logistical assistance. Sarah Carter most ably copy-edited the text and the staff at Jesperson Printing, particularly Cindy Callahan, were very helpful and patient with an ever-changing creation. Dr. John Hewson, of the Linguistics Department at Memorial University, kindly provided the modern Micmac spellings. The people of the Bay St. George Band Council and Micmac people elsewhere on the island provided many years of friendship and a reason for the book. Premier Peckford provided another reason for the book. To all, I owe a great debt of gratitude.

Dorothy Anger

Preface

The Bay St. George Regional Indian Band Council has long been aware of our people's desire to know more about our history. We have been told in surveys, meetings and daily conversation. We know that little research has been done in European written records of our story, and that even less has been published. To date, little that has been published on the history of Newfoundland Micmacs is easily available to us or to Newfoundlanders in general. Over the past decade however, a considerable amount of historical research has been done, usually commissioned by representatives of the Micmac people. That work, which is still far from complete, has shown us that there is a considerable body of early European records of Micmac presence and land use on the west coast.

We decided to have some of these white historical sources compiled and made available to our people. We want to show that our family knowledge is validated by the official white record. We also want to share our history with non-Micmac Newfoundlanders. Finally, through use of primary historical sources, we want to present the record of history to the politicians and policy-makers who attempt to deny our legitimacy as Newfoundland aboriginal people.

We hope that this book fulfills these objectives to some degree and that we continue the research into our past at the same time as we develop our future.

Neil Lucas and Roy J. Gaudon

Introduction

Bay St. George, midway between the Bay of Islands and Port aux Basques, has been home to many different groups of people. It was known to the Micmacs as Noywa'mkisk [Nujio'qonik]* which means "where the sand is blown up by the wind."

The bay was settled at different times by Micmacs, French, Acadians, English, Scots and Jerseymen. When European explorers first visited the coast early in the 1600s, the Micmacs were there. White settlement occurred during the later 1600s and throughout the 1700s. Through the 1800s European settlers increased in number and used more land. The Micmacs were squeezed into smaller and smaller areas in the bay, with their principal settlement being at Seal Rocks in the present-day St. George's.

The white settlement was on Sandy Point, a small spit of land in Bay St. George. In the early 1900s, the white population began moving to the mainland side of the bay, at Seal Rocks, after the railway was built. Soon after, the Micmac community disappeared from the official record. We can assume that the people went further along the bay to Flat Bay and St. Theresa's, which are still predominantly Micmac communities. Others live in St. George's, Stephenville Crossing, Mattis Point, Stephenville, and throughout the Port au Port Peninsula.

European historical sources of our knowledge of the Micmacs are accounts kept by naval officers, explorers, scientists, clergymen and government officials. Samuel de Champlain explored the west coast in 1604, giving us one of the earliest references to date to Micmacs in the area.

*Throughout the book, the spelling of Micmac words from original texts (such as the above from Frank Speck) is followed by modern spelling in square brackets, using the orthography developed by Doug Smith and Bernard Francis of the Micmac Association of Cultural Studies in Sydney, Nova Scotia.

White fishermen, on the west coast from at least the mid-1600s, were interested in keeping alive, not in keeping notes. Most whites who were interested in keeping notes on native people came late in the history of the area's settlement. They travelled about the island in the latter half of the 1700s and early 1800s and confined their explorations to coastal areas.

The European country which had the most contact with the west coast was France. The west coast was French territory until 1904. The Micmacs were allied with the French in Acadia and their friendship continued in Newfoundland. Soon after contact with the French in the early 1600s, the Micmacs adopted the Roman Catholic religion. This and their trade contact were links that were never shared with the British. There was extensive intermarriage between Micmacs and French in Acadia and Newfoundland, something which did not occur until much later with the British. Unfortunately, we have only started to look at French archival records, so we do not know the extent of information in them.

In 1822 William Cormack became the first white man to cross the interior of the island. He, like other explorers, was guided by Micmacs and was primarily interested in the Beothuks and the terrain, but, unlike many of the others, he kept extensive notes on what he learned of the Micmacs.

Stories passed down from generation to generation of Micmacs are an important source of historical knowledge. But oral history has not been greatly relied upon for understanding Micmac history on the island. One reason for this is that academic history in the past has not valued that kind of folk knowledge. Another reason is that many of the stories and traditions have been lost because Micmac identity was considered undesirable for many years.

The word "Micmac" was often accompanied by "dirty," "thieving" or "lazy." After over fifty years of being looked down on, it is surprising only that the Micmac heritage did not die completely in Bay St. George. This has happened with other native groups in the North America, especially on the Eastern Seaboard of the United States.

Instead, a dual reaction to Micmac identity developed. If called a "dirty thieving Indian," many people reacted with a "punch in the face," as some have said. If insult was not meant by the term Micmac, most people took it as a simple statement of fact. With such ambiguity surrounding it, Micmac identity was kept private by most people, remaining alive only within family circles. Many stories have been lost with the death of their tellers, thereby increasing the gaps in our knowledge.

This book is a collection of writings taken mainly from European travelers who came in contact with the Micmacs from the 1600s to the 1900s. Some pieces directly concern the history of Micmac people in Bay St. George, while others refer to Micmacs in other parts of the island. Micmac territory may have been centred in Bay St. George, but they hunted, travelled and lived far north, south and east of there.

In the following pages, there are descriptions of the traditional beliefs and customs of the Micmac people. Not all specifically refer to Bay St. George, or even to Newfoundland. Much more attention was paid by writers of the last century to Nova Scotia Micmacs, which means that many of the best descriptions of how Micmacs lived come from there. Where there are no known differences between the situations in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, we have used Nova Scotian material.

This book includes maps, dating from 1760 to the 1900s, showing continuity of occupation of Bay St. George by the Micmacs, as well as their role in the early mapping of the interior of the island. There are also stories, some written long ago, others written recently, concerning the history of some west coast Micmac families. The people mentioned in this volume are simply a few of the Micmac families who live in the area.

By the way this book is set up, we wish to convey a sense of history as a series of glimpses. One cannot simply start at the beginning of the story and work through to the end. Instead, historical knowledge is like a family photo album; it does not tell later generations everything about the family, but gives snapshots of moments in the lives of people now gone. The stories, we hope, say something about how it feels to be Micmac on the old French Shore, in a Newfoundland which often does not even admit the existence of Micmacs. We think that these voices can speak best for themselves without rephrasing them.

Who are the Micmacs?

The Micmacs of Bay St. George are part of the Micmac nation whose territory extends from the eastern part of Quebec through the Maritime provinces and Newfoundland. Traditionally, they were hunters and gatherers who lived a semi-nomadic life which followed the course of the seasons and the game. They spent the summer months in large villages made up of several extended families at river mouths on the coastline, where they fished and readied their equipment for the winter's hunt. In winter, small family units travelled in the interior, following the path of caribou and fur-bearing animals.

By the early 1600s, the Micmacs had allied themselves with the French. They traded with, and married the French, and mixed Roman Catholicism with their traditional spiritual beliefs. Their relations with the English were quite different, with very few economic or social links. English officials, missionaries and settlers tended to either impose their system on the Micmacs or to keep themselves apart from them. Therefore, due to their own interests and their connections with the French, the Micmacs quickly became enemies of the British.

A history of Micmacs in Newfoundland must consider their traditional use of the island, the most easterly part of their territory, and their relations with the French and English. Micmacs were coming to Newfoundland for varying lengths of time before they had access to French vessels and before the English gave them reason to want to leave Nova Scotia However, when increased British settlement of mainland Nova Scotia and Cape Breton made the Micmacs' way of life more difficult, they started moving permanently to the west coast of Newfoundland in larger numbers.

The first permanent settlements in Newfoundland were in the Codroy Valley and Bay St. George. But their hunting territory occupied a much ' larger area, including the whole of the southern half of the island and the northern half after the early 1800s. As white settlement increased in the Codroy, Bay St. George and Bay of Islands areas, Micmac settlement increased in the relatively unsettled south coast.

At present, they live on the west coast in the Bay St. George-Port au Port area, the Bay of Islands, and the Northern Peninsula; central Newfoundland in Glenwood and Gander Bay; and on the south coast in Conne River. Only those Micmacs living in Conne River are recognised by the federal and provincial governments as being Indian, and that recognition has come only in 1984 with the granting of status under the Indian Act. Micmac people living in other parts of the island are not recognised by either federal or provincial governments, other than by the federal Department of the Secretary of State which provides funding for the Federation of Newfoundland Indians.

The straightforward description of the Micmacs is: people of the Algonkian-speaking Eastern Woodlands native group, with traditional territory in Atlantic Canada. While this description tells us something about the Newfoundland Micmacs, it is only part of a much more complicated story.

The Micmacs in Newfoundland kept in contact with Micmacs in Nova Scotia until early in this century, but lost touch due to pressures from the church and white neighbours. The Micmac language in Newfoundland was lost for the same reasons. Their friendship with the French presented problems for the English who, during the 1700s and 1800s, were trying to establish themselves as the undisputed power in the island. The presence of Micmacs in Newfoundland threatened their control. Judging by the province's reaction to discussion of native rights for Micmacs, that threat to control is still felt by the powers that be.

After the west coast passed to British hands for the last time in 1904, French or Micmac ancestry became a stigma and butt of insults and jokes. As a result, French surnames (of French and Micmac families) were changed to their English versions, either by choice or by English-speaking priests and officials. The Micmac and French languages and cultural traditions were almost lost because they presented more liabilities than benefits in an officially English-speaking society. For both groups, there was a long period of loss of cultural identity.

But the loss was by no means complete, and a level of Micmac identity has remained throughout this century. In the 1945 Newfoundland census, 351 people of a total of 13,074 in the St. George's-Port au Port district declared themselves "French-Indian" or "English-Indian." At a time when the area was fully incorporated into British-Newfoundland society, with absolutely no benefit to be gained by declaring oneself Micmac, such statements say a lot about the strength of Micmac identity.

In the following pages, there are descriptions of the Micmacs of Bay St. George and surrounding area as seen by European travellers. There are also stories of a few Micmac families, which put names and faces to the often unidentified Micmacs described in white sources.

1. The letters below indicate the lack of information available about Micmacs and the belief that there would soon be no differences between Micmacs and whites. Pere Pacifique was a missionary and authority on the Micmac language. James Howley was the government's chief geological surveyor who in his many explorations of the island was accompanied by Micmac guides. If Pere Pacifique were to make his request today, he would still get very few reports on the Newfoundland Micmacs.

Restigouche, P.Q; Canada, March 12th 1902

To the Secretary of the Governor of Newfoundland

Dear Sir,

Though I have not the honor to know you, I hope you will not refuse me a favor. I wish very much to have some information on the Micmac Indians of Newfoundland. There must be a report printed on these matters; I should feel thankful if you were kind enough to send me the last issue, or tell me where I could get it from.

Yours respectfully,

F. Pacifique, 0. M. Cap. Asst. Missionary

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF NEWFOUNDLAND

St. John's, Newfoundland, March 18th 1902

Hugh H. Carter Esq., Private Secretary

Dear Sir

For the information of your correspondent re the Micmacs in this Island, I beg to state that so far as I am aware, no report has ever been made regarding them...

By a reference to the census returns of 1884 and 1891,1 find in the former year there were 202 but in the latter only 123, so they would appear to be fast dying out. I have not the returns for 1901 at hand, I expect these will show a very considerable reduction, and that but very few now remain. They nearly all reside in Bay D'Espoir, Fortune Bay District, but there are still a few in Bonavista, Notre Dame and Bay St. George Districts.

They are all descendents of Micmacs who came over from Cape Breton Island and Nova Scotia, with a few from Labrador (Mountaineers). They were not of course the original inhabitants of this island, being quite a distinct tribe, nor did they ever, so far as we know, intermingle with the original Beothucs.

Now that game and furred animals are getting scarce, I believe the Micmacs' day in Newfoundland is all but over. I do not believe there are 100 now in existence here. Consumption is rapidly decimating them. They appear to be very prone to this disease.

Hoping the above may suffice to answer your correspondent's queries.

I remain, Truly yours,

James P. Howley

Source: Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, GN 1/3/A fl35.

2. Even by the middle of this century, the government knew little more about the Micmacs than did James Howley in 1902. The memorandum below is from correspondence about responsibility for native people between the federal and Newfoundland governments after Confederation. Although the federal government recognised their responsibility toward them, (F. P. Varcoe, Deputy Minister, Department of Justice, April 14, 1950), native peoples of the island and Labrador were not included under the Indian Act.

There were apparently a few hundred Indians and half-breeds living on the island of Newfoundland. These, however, had become pretty well indistinguishable from the white people amongst whom they lived. The real problem was in Labrador...

Sourc:. 1950 Memorandum, Interdepartmental Committee on Newfoundland Indians and Eskimos, Government of Canada. National Archives of Canada, MG30E/159.

3. This piece is a good example of the prejudices, stereotypes and fears with which some whites thought of the Micmacs. There is no evidence of Micmac subjection to the Mohawks and, while Micmacs did seize English vessels in the 1700s, there is no indication that crew members were ever scalped.

The inhabitants of the interior [of Newfoundland], are a degenerate race of Indians-corrupted, as the natives always are by their intercourse with the whites. They are composed of the remnants and descendants of two tribes, called Micmacs and Mountaineers-the Micmacs residing in their groups of cabins on plats of table land in rear of the European settlements, and the Mountaineers, as their name indicates, living further north among the mountains.

They are a hardy and athletic race of savages, resembling the northern and north-western tribes in the United States and Canda. They are extremely jealous and quarrelsome, especially where the fin-water has been among them. But their feuds are generally appeased with blows, and bruises, without the shedding of much blood. Revenge, however, is as sweet to them, and as unerringly follows any real injury, as among the rudest savages of the American wilds. These aboriginal inhabitants of Newfoundland, it is said, were formerly subjected to the Mohawks, one of the most powerful and warlike tribes of the West, and there is a tradition, that until the power of that tribe became extinct, it was a custom with the Indians of Newfoundland to send, at stated periods, a canoe and several men up the St. Lawrence, to pay homage to the chiefs of the Mohawks in Canada. These natives were savage warriors in the time of the French possession of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, and unmercifully massacred and scalped whole crews of English vessels wrecked on those dreary and inhospitable coasts.

Source: 1839 Ephraim Tucker, Fist Months in Labrador and Newfoundland... Summer 1838. Concord: I. S. Boyd & W. White, pp. 44-45.

4, 5. In the letter below and the following story, the Micmacs' contacts with Beothuks an described. The one below refers to Micmacs and other native groups being in the Twillingate ana early in the 1800s in sufficient numbers to worry the Newfoundland government. The next one suggests that the Micmacs did not think highly of the Beothuks.

Fort Tbwnshend, St. John's Mst May, 1819

To the Revd. J. Leigh, Twillingate, to recommend to the Micmac & Esquinaux Indians to live peaceably with the Native Indians.

Sir,

I have to desire you will cause it to be made known in the manner you nay deem most expedient, to the Tribes of the Micmac, Esquimaux and ither Indians frequenting the Northern parts of this Island. That they are not under any pretence to harass or do any Injury whatever to the Native ndians for if they should be detected in any practices of that nature they /ill surely be punished & prevented from resorting to the Island again. tut as they are all equally under the protection of His Majesty's Govenment, it is on the contrary recommended to them to live peacably with the Native Indians and endeavour to effect an Intercourse and traffic with each other.

I am Sir, Your most obedient servant,

C. Hamilton

[Governor of Newfoundland]

Source: Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador, GN2/IA V21 pp. 104-106.

5. June the twenty-fifth [1813] -

The Purser of the ship, and the author, again repaired to the river for trout. We had proceeded but a short distance up the stream... when a musket was discharged in the woods behind us; and, after uttering a loud halloo, an Indian burst through the thicket, with a gun in his hand. At first we did not much relish his appearance, and accordingly caught up our fowling-pieces: but it was impossible to suspect him long; for, with a smile upon his countenance, he advanced gently forward; taking off his cap with one hand, whilst with the other he laid down his musket upon the trunk of a fallen tree. We offered him rum, which, to our utter astonishment, he refused; but he accepted of some biscuit and boiled pork. The following conversation then ensued between us. We first inquired, where he was going, and at what he had fired. "Me go get salmon gut, for bait, for catchee cod. Me fire for play at litteel bird." Observing the word Tower marked on the lock of his musket, we said, "This is an English gun." "May be. Me not get um of Ingles; me get um of Scotchee ship: me givee de Captain one carabou (deer) for um." - "Do you go to-morrow to catch cod?" "Ees: me go to-morrow catchee cod: next day, catchee cod: next day come seven day (Sunday) me no catchee cod; me takee book*, look up God." We asked if the savage Red Indians, inhabiting the interior of the country, also looked up to God: when, with a sneer of the most ineffable contempt, he replied, "No; no lookee of God: killee all men dat dem see. Red Indian no good." - "Do you understand the talk of the Red Indians?" "Oh, no; roe no talkee likee dem: dem talkee all same dog, 'Bow, wow, wow!' " This last speech was pronounced with a peculiar degree of acrimony: at the same tune, he appeared so much offended at our last question, that we did not think it prudent to renew the dialogue. This Indian seemed highly diverted at seeing us catch the largest trout with such small rods, hooks, and lines; and he left us a short time afterwards, in great humour.

* None of the Indians in St. George's Bay are able to read; but they have been taught almost to adore the Bible, by some French missionary. [Chappel's note]

Source: 1818 Lieut. E. Chappel, Voyage of HMS Rosamond to Newfoundland and the Southern Coast of Labrador. London: J. Mawman, pp. 69-72.

6. Then an reports, like the one below, which speak ofMicmacs' marriages to Beothuks. Harry Cuff, in the November 1966 Newfoundland Quarterly told the story of Anne (Gabriel) White of Stephenville who says that her great-grandfather was a Beothuk married to a Micmac woman. Historians say that then was no intermarriage between the two groups, but family histories, such as the one below, suggest then was. It is difficult to prove unless family history is accepted at face value. Unfortunately, the idea of having a Beothuk ancestor is romantic, making it difficult to sort out probable ancestry from fanciful. An interesting point in this story is that a Beothuk name for Micmac territory in the island is given.

The Rev. Silas Tertius Rand... said the story was related to him by one Nancy Jeddore (Micmac) of Hantsport, N.S., who received it from her father, Joseph Nowlan who died about fiteen years previous, at the advanced age of ninety five years...

"The Micmacs time out of mind have been in the habit of crossing over to Newfoundland to hunt. The Micmac name for this large Island, is 'Ukta-kumk' [Ktaqamk], the Mainland, or little Continent...

"The name," he says, "seems to indicate that those who first gave it had not discovered that it was an Island. The Micmacs who visited it knew that there was another tribe there, but never could scrape acquaintance with them, for as soon as it was known that strangers were in the neighborhood, these Red Indians- ... who were believed to be able to tell by magic, when anyone was approaching-would gird on their snow shoes, if it was in the winter season, and flee as for their lives. But on one occasion three young hunters from 'Megumaghee,' Micmac-land-came upon three lodges belonging to these people. They were built up with logs around a 'cradle hollow,' so as to afford a protection from the guns of an enemy. These huts were empty and everything indicated that they had just been abandoned. The three Micmacs determined to give chase, and if possible overtake the fugitives, and make friends with them. They soon came sufficiently near to hail them and make signs of friendship, but those signs were unheeded, and the poor fellows, men, women, and children, fled like frightened fawns... Nothing daunted, however, the young men continued the pursuit. Finally one of the fleeing party, a young woman, snapped the strap that held her snow-shoe. This delayed her for a few moments... Her father ran back to her assistance and she was soon again on the wing. But the mended strap again gave way; and by this time the pursuers were so near that the poor creature was left behind, her companions would not halt for her. She shouted and screamed dolorously but her shrieks and cries were unheeded, and she was soon in the hands of the three hunters. They endeavoured to make her comprehend that they were not enemies but friends, that they would not injure a hair of her head. But although she probably understood the signification of their gesticulations, she had no confidence in them. She resisted wildly all attempts to lay a hand upon her and cried and shrieked with terror whenever one of them came near her. They tried to induce her by signs to go back with them to their encampment, and that she should be kindly treated and cared for. But this she positively refused to do. They offered her food which she refused to touch. Night was coming on and her friends were evidently now far away. The hunters could not leave her there to perish so they constructed a shelter and remained at the place for several days. Finally they succeeded in some measure in pacifying her. Of one of the young men she ceased to be afraid. She went back with them to their camp, but still for several days refused all nourishment, but she clung to the young fellow who had first won her confidence, keeping as far as possible from all the rest... After a few days, however, she became pacified, and after remaining with them two years, she had learned to speak their language, and became the wife of that one other captors to whom she had first become reconciled. Then she recounted her history. "Joseph Nowlan, my informant's father, saw her many a time, and conversed with her on these subjects, but these details are lost. One summer when on the Island [of Newfoundland], Nowlan boarded with the family. The woman became the mother of a number of children..."

SILAS T. RAND Hantsport, N.S. May 21, 1887.

Source: 1915 J. P. Howley, The Beothuks or Red Indians. Cambridge University Press, pp 284-286.

7. Below is an example a/continued contact between Micmacs a/Newfoundland and Cape Breton even during times of cultural pressures, such as when Nova Scotia Micmacs wen concentrated in two reserves in the interests of service provision. It gives an alternate explanation of the Newfoundland Micmac name of Gabriel than is given in Mrs. White's story, referred to in number 6 above, who said that her great-grandfather, named Gabriel, was a Beothuk. There is also a reference from 1799 in the Massachusetts Historical Society Collections (Series I, v. 6. p. 16) to "Gabriel, a young Mountaineer Indian (servant to Louis, a Micmac, in the Bay of St. George, Newfoundland) "

Mr. Frederick Gabriel of Eskasoni, Nova Scotia, believes he is related to the Stephenville Gabriels directly. He mentioned frequent travels of the Nova Scotia Gabriels to Newfoundland throughout the years of centralization [1950s].

He also tells of how the name Gabriel was acquired by the Scotian Indian family. It seem his grand-father was nicknamed "Old Gable," but when the Christian missionaries began their work in Nova Scotia, they mistook the pronunciation for Gabriel and considered him Gabriel from then on.

Source: 1977 Lori Sparkes, Comer Brook, research for the Federation of Newfoundland Indians.

8. The story below shows the kinds of confusion about family origins which can result when information is accidently or deliberately lost to later generations. The writer sees no evidence of Micmac ancestry in the Webb family. If their family tree is drawn, as on the next page, and compared with Speck's list of hunting territories it is easy to see Micmac ancestry. John Webb's mother, Bridget Benoit, was the sister of Peter Benoit. Another brother (overlooked by Lori Sparkes) was the Paul Benoit mentioned by Speck. Speck says Paul Benoit is of Micmac and French descent. Other sources, and community knowledge, identify Paul and Peter Benoit as Micmacs.

John Webb came from Baie d'Espoir and his wife came from Conne River. Mr. Webb, as far as anyone knows, was a trapper and fisherman. [His brother Charles] Webb married Alice George from Bonne Bay.

Copyright ฉ 2002-2003 Jasen Benwah

Thanks for Dropping By