N0YWAMKISK

(Where the Sand Blows...)

Vignettes of Bay St. George Micmacs

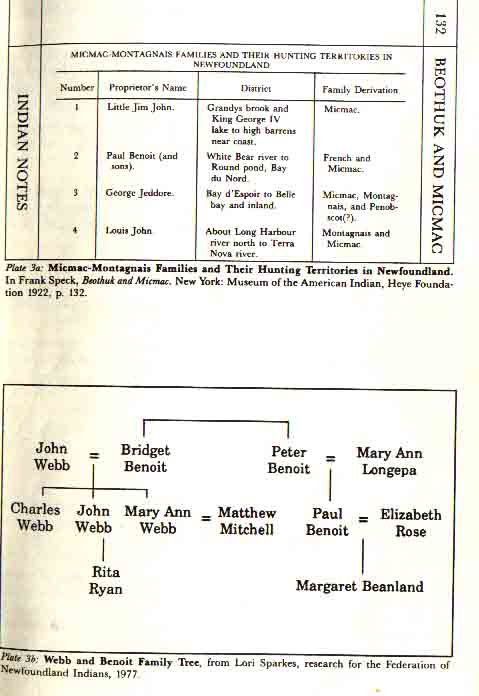

There was no Indian on the George side of the family. Unless there was Indian on Mr. Webb's mother's side of the family there is no proof of Indian in the Webbs that I could find yet. [John Webb's daughter, Rita] Ryan told me that her mother was Indian and her father was French. She said as far as she knew her father was French. Unless there was a Webb that married an Indian, she said they were French. She told me that her mother was a Micmac Indian from a Sydney reserve. Mrs. Beanland of Flat Bay is the daughter of Paul Benoit and Elizabeth Rose and her grandfather was Peter Benoit and Mary Anne Longepa (grandmother).

Peter Benoit, Mrs. Beanland's grandfather, and Bridget Benoit were brother and sister. Bridget Benoit married John Webb and was the mother of Mary Anne Webb and Charles Webb [and John Webb]. Mary Anne later married Matthew Mitchell...

Mrs. Beanland said that her grandfather, Peter Benoit, was the first settler on Sandy Point along with another man named Perrier and that before Mr. Benoit lived in Sandy Point he lived in Margaree in Nova Scotia. Her grandmother, Mary Anne Longepa was of Portugese ancestry. Paul Benoit, Mrs. Beanland's father, was the first line repairman in the area and he also trapped in his spare time. Her mother, Elizabeth Rose, had at one time worked in Conne River for a Mr. Small who was the telegraph operator at the time.

Source: 1977 Lori Sparkes, Corner Brook, research for the Federation of Newfoundland Indians.

9. This passage suggests that maybe European spouses did more adapting to their partners' Micmac way of life than the other way around. The families described her may have been Brakes, mentioned by name in the following pieces.

[August 17, 1839] Where we lay last night there was no sign of habitation ... Just at the mouth of the [Humber] Sound, however, we saw a small hut and made toward it and presently a human figure presented itself in tattered dress.

But it was not until we heard him speak that we knew whether he was an Indian or European. We found him to be an Englishman, who, with his wife and two children, had just settled there and that this hut was his summer residence; his winter house being back in the woods.

On the opposite side of the Sound to the old man's house we found an Indian wigwam with an old Indian woman and her two daughters, one of the latter of whom had a daughter married to one of the old man's sons opposite. The old woman had a kind of moustache tattooed on each cheek and spoke nothing but Indian, but one other daughters could speak English. They were busy making baskets and moccasins and were very neat, tidy and civil people...

Source: 1842 J. B. Jukes, Excursions In and About Newfoundland During the Years 1839 and 1840. London: John Murray, p. 113.

10, 11. The following two selections an about the Brake family of the Bay of Islands. They show another difficulty in documenting Indian ancestry on the west coast, in not giving names of Micmac women. The next piece (^14) calls the woman the daughter of "Captain Jock" probably Mattie Mitchell's great-grandfather.

As we sailed onwards we observed that both sides of the river were studded by numerous salmon nets in many of which the silvery captives plunged... These nets belong to a family of the Brakes who live further down the river. They maintain themselves entirely by the salmon and trout fisheries... The Brakes, from long occupation, have acquired a kind of prescriptive right to the fishery in this river; and, whether it be according to law or not, one fact is certain that no one else dare have a net in the river. The Brakes are a powerful body of men and trust to their own right arms to defend their claims.

The progenitor of these men came out from England over 100 years ago, he located himself on the banks of this river far away from the haunts of men and lived a semi Indian life, trading in furs and salmon and deer flesh. TO complete his felicity he married a squaw, probably following the darwinian theory of natural selection, from whom there sprung up the present 10 or 12 families. They have divided into two parties on account of some dispute concerning a box of money stowed away by their first parent... This little incident gave rise to a separation among the families who thence forward occupied different sides of the river, and to this day live in a bliss-

ful state of family feud, quite romantic and smacking of the middle ages, manifesting itself periodically in the shape of disputes about the boundaries and rights of fishing &c.As we advanced up the river, there suddenly shot out from behind a wooden peak a small boat, which darted swift as lightening from us. It was manned by one individual of every extraordinary appearance. The features presented a very marked type of the Micmac Indian, an enormous crop of coarse, bushy red hair stood out thick and matted upon his head, while a very sparse down of the same roseate hue flourished undisturbed upon his face and chin... This person was one of the Brakes, the owner of the net whose burthen we had kindly lightened awhile previously. He appeared very much awed by the sight of so many human beings, in this solitary haunt, and seemed anxious to avoid us, and escape into one of the creeks by the riverside...

Source: 1871 " 'Reminiscences of a Trip to the Western Shore of Newfoundland,' A Lecture. .. by Rev M. F. Howley, D.D.," Terra Nova Advocate, 23 February 1882. Newspaper Collection, Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador.

11.Thursday, August 2d. [1849] - ... we proceeded to Tucker's Cove [Bay of Islands], where the children of J. Brake were baptized.. .His wife is an Indian from St. George's Bay...

Friday, August 3d. -We went... to visit a family who had returned from the fishery yesterday evening. The man is a Brake, brother to the Brakes mentioned before. The mother is a Micmac Indian from St. George's Bay. She appeared a notable, sensible woman, and she assured me she could repeat the Lord's Prayer and Creed in her own language, with other prayers. Her father, she said, was Captain Jock. Four of their children were baptized with the conditional form. The mother assured me the baptism among her people was precisely the same... Saturday, August 4d.-We stood in to Mac Iver's Cove, and I visited the settler, one Park... His wife is an Indian from Burgeo...

Source: 1650 Bishop E. Feild, Journal of a Voyage of Visitation in the "Hawk" Church Sloop... 1849. London: Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, pp. 47-50.

12. On the previous page is a copy of the Lord's Prayer and Creed in Micmac, also mentioned in number 11. In his letters below, Thomson describes the Micmac way of writing, and the importance placed on being able to read and write. It is interesting that at this relatively early date-the end of the 1700s-some Micmacs in Newfoundland were literate in their own language.

His Majesty's Sloop Fly, Plymouth Sound, 13th November '91 [1791]

Sir-

I beg leave herewith enclosed to send you the Lord's Prair & Creed, written by the Native Indians of Newfoundland, which they did it with a stick made in the shape of a pen. The Creed marked Number One, the Prair No. 2. I beg leave, Sir, to observe it the Roman Catholic Prair & Creed, as the Frenchmen have intermarried with those Indians.

I have the honor to be Sir,

Your very humble servant

John Thomson, Midshipman

HMS Fly

[To] Sir Joseph Banks

Sir-

I this day had the Honor of your favour, and beg leave in reply to Acquaint you that it was wright by those Indians; and Sir they have amongst them a Schoolmaster to instruct their children in Wright and read, and on my making a Penn for them they prefer'd the Stick. There is in every family a large Book made out of the Bark of the Birch tree written I should suppose Century back. If these informations is of any Service, it will give much Pleasure. I beg to observe, I offered any price for one of these Books, but they would not part with them upon any account... I have the Honor to be Sir,

Your most obedient

John Thomson

[Ib] Sir Joseph Banks

Source: British Library, Add. ms. 11038, fo. 13-16.

13. Mattie Mitchell is probably the best-known Micmac and hunter in Newfoundland. The writer of this story is one of his many descendents.

Matthew Mitchell was born in Newfoundland in the mid 1800s. He was a Micmac Indian and it is presumed that his ancestors came from one of 20 the Maritime provinces. He was a very tall, dark-skinned man with typical Indian features. He married the former Mary Ann Webb from Flat Bay. They had six children. They are Lawrence, Matthew, John, Bridget, Lucy, and Margaret. These children were all born in Bonne Bay where Matthew and his wife settled.*

He was a trapper and a hunter by trade and he spent a great deal of his life guiding foreign sportsmen through the country... He also did survey work for the I.P.P. Company here in the surrounding area of Corner Brook. The company is now known as the Bowater Paper Company. He also did Mineralogical surveys and it was in 1895, while he was employed with the AND Company that he discovered the "Mineral find" that later became known as Buchans Mining Company...

After his wife Mary Ann died, his son Jack... lived with his father. Agnes [George] Mitchell recalled when her father-in-law Mattie came back from one of his trips to the country and he had with him some pearls that he found in some clams. She says that he got the sum of $700 for them.

He was so extensively known as a guide that he was asked to guide the party of men that were introducing the reindeer to Nfld. The trek must have been an arduous one as they travelled about 400 miles overland till they arrived at their destination with the Reindeer...

Matthew Mitchell was a devout Roman Catholic, he had prayer books written in Micmac and French simultaneously... One of his final requests was that the Monsigneur [Curwen] be sent for. At that time the priest was living in Curling and the only means of transportation was by boat. So his son Jack got a small dory and rowed to Curling and brought the priest to his father's bedside just before he passed away.

Source: 1977 Lori Sparkes, Corner Brook, research for the Federation of Newfoundland Indians.

14. Below, Chappel describes the Micmac and white communities at St. George's. Some accounts sound as if the two groups kept very separate, with the Micmacs simply waiting at Seal Rocks to be visited by Europeans. However, Chappel's account describes a much more active role played by the Micmacs, including taking up arms to defend their community.

June the twenty-third [1813]-Towards evening, we anchored off a small village, called Sandy Point, at the bottom of St. George's Bay... Immediately opposite to the village of Sandy Point, stood a village of about twenty Indian wigwams.

Mr. Massery [Messervy], the constable and chief man of this place, came on board, with information that the whole of the settlers in St. George's Bay had for two days been kept in a state of the greatest alarm, in consequence of their having mistaken our ship for an American cruizer. Precautions had been taken against a surprise; and the whole of the Indians on the opposite side of the bay were actually under arms, to oppose our landing. However, we soon succeeded in quieting their fears; and upon hoisting our Union-Jack at the main-top-gallant-mast head, we received a visit from the Chief of the Micmac Indians... '

Independent of the colony of Micmac Indians, there are, in St. George's Bay, thirteen families of Europeans, or their descendants, who have been born in this place. Owing to a contrariety in their religious opinions, eleven ' of them are called English families, and the remainder are denominated French; the former styling themselves Protestants, and the latter Catholics. We inquired into the method of performing the marriage ceremony, and , interring the dead: and were informed that the Crusoe-looking being, whom we had met with upon first entering the place, possessed a licence from ''' St. John's, to perform the functions of a priest. "He was the only person residing there," they said, "who knew how to read!" and he officiated at all the religious ceremonies of both Protestants and Catholics.

The whole of the white population did not amount to more than one ., hundred and twelve persons: and estimating the Indian colony at ninety-seven, St. George's Bay may be said to have contained about two hundred > and nine souls altogether, including English, French, Indian, women and children.

Source: 1818 Lieut. E. Chappel, Voyage of HMS Rosamond to Newfoundland and the Southern Coast of Labrador. London: J. Mawman, pp. 66-67, 85-87.

What did they do?

The Micmacs traditionally were hunters and trappers. From autumn through spring they lived in the interior of the island following the caribou herds or tending trap lines. In early times, before contact with the Europeans, the Micmacs would spend the winter months in the interior in small groups of one or two families moving in pursuit of the caribou. In the spring they moved near the coastline, to river mouths where salmon and eels were plentiful. There, several families joined together to form large camps. The summer, with plenty of food available, was a time for festivities, visiting with other families, and preparing equipment for the coming winter.

With increased contact with Europeans, this pattern of life changed. Trapping became more important in order to obtain cash to buy tools, blankets and other trade goods. Winter camps were moved less often because the primary business became maintaining trap lines rather than following caribou herds, which were getting smaller due to increasing white development. Eventually, as Micmacs settled in year-round communities, the men alone would go into the country while the women and children stayed in the settlement.

A system of defined hunting areas held by specific families probably existed among west coast Micmacs, as it did in Badger's Brook, Hall's Bay and Conne River until the early 1900s. Men who trapped in the early 1900s say that a more informal approach was used then, in which during a particular year two partners would use a certain area and others stayed away from it. The only unbreakable rule was that if you saw another man had a trapline in an area, you did not trap in what was, for that time, his territory. White trappers in Bay St. George, in general, respected the Micmac system of land division and many trapped with Micmac men.

The tools of the trade for Micmac hunters were quite simple, but their manufacture and upkeep required great skill. Several methods of transport were needed in the days before snowmobiles and fibreglass canoes. A caribou skin canoe was an easily made way of travelling on inland rivers which could be left by a river when it was no longer needed. Another one could be made at the next river crossing. Birch bark canoes were more time-consuming to make, but were needed for travelling longer distances, especially in open waters. Snowshoes were a necessity for any winter travel by foot. Moccasins were made for a variety of weather conditions. Tanned caribou hide, with or without the hair, was good for moccasins and shanks to wear in dry snow, but they would get soaked in wet snow. For that, "green" or untanned skin boots were best. These boots were kept outside because, when frozen, they were well-insulated and waterproof. Packs were carried on the back with straps woven of caribou hair.

Before European iron, cloth and tools were available to the Micmacs, caribou hide, hair and bones, birch and spruce trees provided virtually everything that they needed to live. Animal hair, paint, and later beads and ribbons, provided decoration. Baskets made of spruce root or wood splints were used for collecting berries, shellfish, vegetables, and for storage.

The art forms and decoration methods of Newfoundland and Nova Scotia Micmacs differ due to availability of materials. Historically, mainland Micmacs were noted for the high quality and intricacy of their quillwork embroidery. In Newfoundland, the absence of porcupines meant that quill-work required imported quills. Instead, moose hair embroidery was done, and later European beads were used. Another example is basketmaking. In Nova Scotia, the usual material used for weaving baskets was ash splints. But the absence of ash trees or any suitable alternative meant that Newfoundland baskets were woven out of spruce root. Newfoundland Micmacs also relied less on birchbark than did their mainland counterparts.

The old way of life is not that long dead for west coast Micmacs. They were still living in wigwams until the mid-1800s. At the turn of this century, they still wore traditional clothing, according to Frank Speck. Moccasins and shanks continued to be worn until the 1930s and 1940s, when equally useful rubber boots became readily available. The selectivity of history had its effect on the numbers and types ofMic-mac objects which remain in Newfoundland. Accidents of history, and lack of attention, mean that there are few old Micmac artifacts of any kind in the collection of the Newfoundland Museum. Anthropologists like Frank Speck and Frederick Johnson collected many items here but took them home to museums in the United States. Other objects, such as a canoe collected by Howley, were lost in the period from 1934 to 1957, during which the Museum was closed. Artifacts may have been incorrectly identified as Beothuk or anything other than Micmac. One example at the Newfoundland Museum is a small Newfoundland Micmac birchbark container. It was catalogued as Beothuk until just a few years ago when it was recognised to be Micmac in origin.

In this section, we look at how some objects on which Micmacs depended were made. But before the descriptions of actual manufacturer, there are selections which describe the world in which the Micmacs lived until this century. Other pieces describe skills of the Micmacs, such as their keen senses and ability to know and remember the land without benefit of compasses and maps. these mental and physical skills were more important to a hunter's success and survival than the objects with which he worked.

1. The following is a description of the Micmac winter hunting pattern, based on oral accounts gathered in 1838 by Tucker in Bay St. George.

As soon as the fishing season terminates, in the month of October, the inhabitants make preparations for their hunting excursions during the long winter that is to succeed. The forests among the mountains afford shelter for numerous bears, wolves, caribou and foxes. To these retreats the hunters repair in companies of from four to twenty, carrying along with them the provisions necessary to satisfy their hunger, and blankets wherewith to shelter themselves during the long winter nights among the mountains. They hunt during the day, separating at short distances one from another, so as to be within hail in case of emergency. As night approaches, they assemble together, scarcely ever failing to bring in some trophy of the chase. Their temporary tent is constructed out of the limbs of trees, and bushes bent together, and covered with boughs, and sometimes with banks of snow, scraped out from the flooring of the hut, and thrown up around the rude habitation. A blazing fire is kept in the interior, the smoke of which passes through an aperture left in the top, and the weary hunters, after partaking of refreshment, and thawing off the icicles from their buskins, roll themselves up in their blankets, and lie down to rest upon the pine boughs surrounding their blazing fire. Within four or five days, usually, the party of hunters will have gathered together as many skins of the animals slain as they can well carry, and they then take up their trail homeward. The carcasses of the slain, with the exception of the caribou and bear, are left to be devoured by other animals... themselves perhaps to be subjected to a similar fate...

Source: 1839 Ephraim Tucker, Five Months in Labrador and Newfoundland... Summer 1838. Concord: I. S. Boyd & W. White, pp. 53-54..

2. This story illustrates why Micmacs were the guides in hunting expeditions and Europeans were the guided. o o oJoe [a Micmac guide] got the best of me that day to the extent of twenty-five dollars, the villian. We had walked for hours without seeing a thing, when he remarked in a casual manner, 'You have not seen no bears, have you, since you came in the island?' 'No, Joe,' I replied, 'not even a sight. I should have thought bears would have been plenty enough; there is lots of feed for them, goodness knows, for the whole barren is covered with blueberries; but they seem to be very scarce.' 'Yes,' answered Joe, 'bear's awful scarce in Newfoundland, but I think I know a place where we might find one, only I ain't got much time; want to get back to my beaver trapping, you know. What you give me if I show you a bear?' 'Oh, well,' I said, 'I don't know; there is no chance of that now; but I would give a five-pound note for a shot at a bear if we had time to look for one.' 'All right,' said Joe; 'suppose I show you a bear within shot, you give me five pounds, eh?' 'Yes, Joe, certainly I will,' replied I. 'That's sure, eh?' 'Yes.' 'Well, look yonder.' And following the direction of Joe's extended hand, I saw a little black speck moving about near the summit of a neighbouring mountain. 'Oh, I say, Joe, that is rather too bad,' I remonstrated. 'I could have seen him just as well as you, and got up to him too, for that matter. However, a bargain is a bargain, so let us go for him.' The ground was very bare and open, but Bruin (or 'Mouin,' as the Indians call him) was so busily engaged eating blueberries, that he allowed us to crawl up pretty near...

Source: 1881 Earl of Dunraven, "A Glimpse at Newfoundland," in The Nineteenth Century January, p. 99.

3. The Earl of Dunraven's description of the Joe family of Halls Bay shows respect for their abilities in the woods. But he mocks their way of describing the land because it is not understandable to people, like him, who rely on compasses and maps.

We tried hard to obtain the services of some able-bodied Joe, but they were all bent on going into the woods to hunt beaver on their own account, and nothing would induce any of the men to take service with us. We might have had our pick of the women, and we regretted afterwards that we had not engaged a couple of girls. They are just as well acquainted with the country as the men; they can paddle a canoe and do all that a man can, except carry loads, and are able to fulfil certain duties that a man cannot- for instance, they can cook, tan hides, and wash and mend clothes, We often regretted afterwards that we had gone into the country without a guide... it is so difficult for a white man to understand an Indian's description of a country, that my ideas on the subject were very vague and hazy. An Indian thinks little of the points of the compass, and uses them very inaccurately. He seems to rely rather upon the prominent landmarks and principal features of the country to find his way about, and attempts to

explain the route by reference to solitary pines, high hills, hard wood ridges, swamps, and streams.

Copyright © 2002 Jasen Benwah

Thanks for Dropping By