N0YWAMKISK

(Where the Sand Blows...)

Vignettes of Bay St. George Micmacs

An Indian once boasted to me of the variety of his language, and affirmed that he had at least two words for every idea. "Always, everything, two ways me speakum," said he. But this is not literally true; though I will not affirm that it is not as correct as some of the "General Rules" we meet with in other Languages.

Source: 1850 Silas Rand, iSTior? Statement a/Facts relating to the History, Manners, Customs, Language, and Literature of the Micmac Tribe of Indians, in Nova-Scotia and P. E. Island. Halifax, N.S. pp. 18-19, 20.

In some cases, the Indians we are describing prove excellent surgeons, particularly in their treatment of cuts, ulcers, and bruises; but they have not the slightest idea of the means necessary to be pursued in setting a dislocated joint. Their skill in medicine is likewise very trifling. The climate produces but few diseases; and they are consequently but little acquainted with remedies*.

* The following additional remarks concerning the Micmac Indians were communicated to the author by John Duke, Esq. Surgeon of the Rosamond... "I do not remember observing any acute or even chronic diseases amongst them. We were much struck at the care and tenderness evinced by the younger part of the community towards those who, from infirmity or age, were rendered incapable of assisting themselves. I saw several instances of old persons unable to walk, and deprived of sight or hearing, who appeared to be regarded by the whole tribe as objects most worthy of their attention.

The first request made by their Chief to me, was for a lancet; and I was surprised to observe that they could use this instrument, in bleeding, with some skill and adroitness. Upon the whole, I am inclined to think that they enjoy, in general, excellent health." [Chap-pel's note]

Source: 1818 Lieut. E. Chappel, Voyage of HMS Rosamond to Newfoundland and the Southern Coast of Labrador. London: J. Mawman, pp. 84-85.

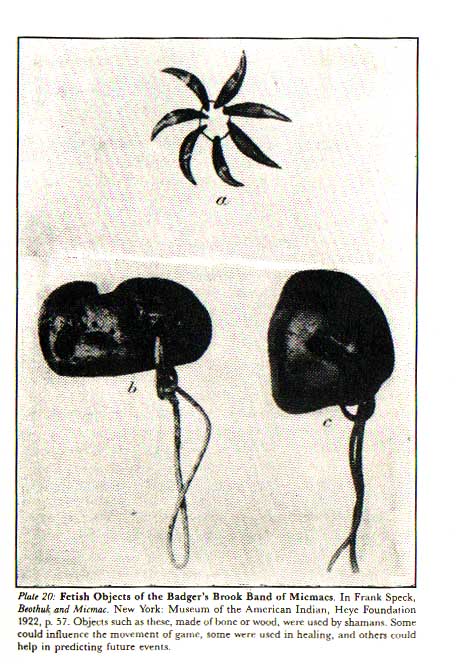

10. The following piece discusses the abilities and methods of Micmac shamans. They acted as doctors, finders of game, and prophesiers.

... When sick, they send to one Sagamore Memberton a conjurer, who prays to the Devils, blows upon the party, cuts him and sucks the blood; he heals wounds in the same manner, applying a round slice of beaver stones, for which they present him with venison or skins. They consult the devil for news, who always answers doubtfully, and sometimes false. He also directs them where to find game when hungry, and if they miss, he excuses it by saying, that the beast changed place; but most times they succeed, which makes them believe the devil to be God. The conjurers when they consult, fix a staff in a pit, and invoke Satan in an unknown language, with so much pain till they sweat again: Then the wizzard persuades the people, that he holds the devil fast with his cord, forcing him to answer; then he sings to his praise for his discovery, which is answered by the savages dancing and singing in a strange tongue; after which they leap over a fire, and put a pole out of the top of the cabin with something on it which the devil carries away. Memberton wore a triangular purse about his neck, with something in it like a nut that he called his spirit."

Source: 1839 Ephraim Tucker, Five Months in Labrador and Newfoundland... Summer 1838. Concord: I, S. Boyd & W. White, pp. 48-49.

11. This story of a wedding describes the difficulty in obtaining the services of a priest when living in a remote area, a problem which still exists in many Indian and white communities.

The sole representatives of the Joe tribe left at home on the evening of our arrival were an old woman and two girls of about eighteen or twenty, whose clear complexions and good features I must suppose were to be accounted for by some mysterious influence exercised by the superior over the inferior race, for I should be sorry to indulge for a moment even in speculation which might be derogatory to the conduct and character of former generations of Joes.

On inquiry, we found that most of the family had gone off some days before to the copper mines, to solemnise the wedding of a couple of fond and youthful Joes, and were expected home that night. About midnight they returned; two large whale-boats full of them, rather noisy and very jovial. The unfortunate but loving Joes had not succeeded in getting married, as the priest, who was expected to arrive by the coastal steamer, had failed to put in an appearance; but nowise discouraged by their untoward event, the party had consumed the wedding breakfast, wisely deciding that the ceremony might keep, but the viands would not. The bride and bridegroom bore their disappointment with a philosophical composure to be found only among people who attach no value whatever to time. In answer to our condolence they replied, 'Oh, no matter; mebbe he come next steamer, mebbe in two, three months, mebbe not come till next year,' and dismissed the subject as though it were a matter of no importance whatever to them.

Source: 1881 Earl of Dunraven, "A Glimpse at Newfoundland," in The Nineteenth Century January, p. 94.

12, 13. Chappel below describes the effects of alcohol on Micmac society.

The Micmacs are, in their dispositions, naturally good-natured, and exceedingly civil towards strangers; but when intoxicated, their whole manner changes. Spirituous liquors, of which they are excessively fond, will, in an instant, convert a peaceful and inoffensive Indian into a most ferocious savage. The women and children are then compelled to seek refuge in the woods. The barbarian, not finding any person on whom he dare wreak his brutal vengeance, will attack his own wretched wigwam, break every article it contains, and probably complete the wreck by tearing the whole fabric to the ground; nay, even the barrel of his musket is frequently bent double, and the stock broken in pieces although he generally esteems his fowling-piece as more valuable and dearer to his heart than either his wife or his children.

If this infuriate maniac be visited on the following morning, he will be found sitting upon the ground, with his family around him, lamenting, in bitter terms, the effects of his preceding debauch. Nevertheless, they have a wonderful facility at repairing the damages occasioned by their frequent fits of intoxication: the wigwam is easily rebuilt, the broken utensils are quickly mended, the musket stock is bound together with slips of raw hide, and the barrel is twisted and bent upon the knee until it is found to carry correctly towards its aim*.

Murders are very uncommon amongst this people; but broken heads, loss of eyes, and deep cuts, are frequently inflicted during their drunken quarrels... although they be implacable in revenging a deliberate insult, yet they have never been known to resent the provocations of an intoxicated man. "Should we blame or punish him," say they,

"when he does not know what he is about, or has not his reason?"

* One of the Indians visiting the Rosamond... was requested to exhibit his skill as a marksman ... Accordingly, he went to the arm-chest to select a musket for this purpose... At length, taking up a marine's firelock, he held it to his eye, to see if it were perfectly straight; then, shaking his head, he took the barrel out of the stock, and repeatedly bent it, in different directions, over his knee: afterwards, he replaced it in the stock; and then, walking forward with a confident air, he levelled the piece, and, in an instant, shivered the bottle to atoms. [ Chappel's note]

Source: 1818 Lieut. E. Chappel, Voyage ofHMS Rosamond to Newfoundland and the Southern Coast of Labrador. London: J. Mawman, pp. 79-82.

13. Below, Tucker describes festivities, in which he unwillingly took part, that occurred when supply ships arrived. Twice a year the merchant ships arrive from England with cargoes of dry goods, groceries, &c. And on the arrival of one of these vessels, the Indians, who are looking for their expected supplies, flock down to the shore, and have a grand holiday. Dances, games, frolic and fun are the order of the day, until the goods are unpacked, and each purchaser receives his half-yearly supply. Happening to be on shore during one of these gala days, a sagamore informed me that there was to be a dance in the evening, and pressed me to join the ring. I declined his invitation, being not over anxious to expose myself to the rude ceremonies of such an occasion. The old fellow was not to be put off, and grasping me round the waist, with rather a herculean squeeze, he carried me into the midst of his company, nolens volens. Seeing that he was already under the influence of liquor, and probably not to be trifled with, I thought it the "better part of valor" not to attempt an escape. I did not, I confess, exactly like the company into which I was so unceremoniously thrust... I took a seat in one corner of the room to observe the ceremonies of the dance. An old Indian soon took his stand in the middle of the floor. His stature was small, but with a body disproportionately stout and thick. A white blanket hung loosely upon his shoulders- under which a long hempen frock extended down to his knees. He had on a sort of loose trousers of half dressed leather, and buskins of undressed seal-skin. He had a sort of hat upon his head, made of the skin of some sea fowl dressed with the feathers on. In each hand he held a stick some ten or twelve inches in length. Thus accoutred he commenced the evening ceremony by a monotonous song, the words of which were totally unintelligible to my ear, keeping time with his feet, and striking his sticks rapidly together, and producing a prodigious clatter. Even and anon a loud yell was uttered by the performer, whereupon the whole circle joined in the chorus. The noise and the merriment increased until all were heartily engaged with shuffling feet, and voices strained to the utmost. An hour of these rough and tumultuous sports, was sufficient to satisfy my curiosity, and I left them at their merry making, which was continued far into the night, ending, as usual, in riotous and beastly intoxication.

Source; 1839 Ephraim Tucker, Five Months in Labrador and Newfoundland. . . Summer 1838. Concord: I. S. Boyd & W. White, pp. 50-52.

14. The passage below shows that, although Europeans and their way of life had gone quite a way toward destroying Micmac culture, they had not completely succeeded. It is also related that in olden times the priest had to be careful what they did because the buowin caused them all kinds of trouble. For example, a shaman named Gabriel caused the ship, in which a priest was travelling, to sail backward so that the cleric could not go where he wanted. The priest, in order to reach his destination, had to "make friends" with Gabriel.

Source; 1943 Frederick Johnson, "Notes on Micmac Shamanism," in Primitive Man 16:3 and 4, p. 78.

Conclusion

The writings presented here show a continuity of Micmac presence on the west coast of Newfoundland from the time Champlain wrote in 1604 through to this century. They traded with the French and English, fought alongside the French and made their peace with the English, were ignored by later governments, and were relied on for information and help by white explorers of the island. During this century, their way of life changed to accommodate white development and a new wage economy. Their language and many of their traditions were lost because of prejudice and the new social and economic order. But the thread of Micmac identity continued to remain alive throughout the years, and in the past fifteen years has found expression in political organisation.

In 1972 the Micmacs of the island joined with the Innu and Inuit of Labrador in a native association. During the following years, that association separated into three, and then four, groups. Now, the Micmacs of the west coast and central Newfoundland are represented by the Federation of Newfoundland Indians and by regional band councils.

These organisations seek political and economic benefits for their members, and work toward a revival of their cultural traditions and historical knowledge. This work has been done often against great odds, with little support from the government and non-governmental agencies concerned with such matters. Except for non-status funding from the Department of the Secretary of State, members of the FNI and band councils receive no funding, support or official recognition from the federal government.

Negotiations between the federal government and the Micmacs for registration under the Indian Act took from 1978, when the government first agreed to give them status, until 1984 when the Conne River Band was finally registered. The federal government has made few serious attempts to deal with the question of registration and funding for west coast and central Newfoundland Micmacs, let alone consider land claims of theirs. The provincial government has refused to recognise Newfounland Micmacs and has actively worked against their registration under the Indian Act and land claim.

The province bases its argument against the Micmacs on the premise that the Micmacs came to Newfoundland after settlement by Europeans and therefore are not entitled to any rights here. Premier Peckford, in December of 1987, said that his family had been here longer than the Micmacs had been. We hope that some of the writings here induce him to visit the Provincial Archives to check the accuracy of his history.

Unfortunately, the lack of information about the early history of Micmacs in Newfoundland encourages such thinking as Premier Peckford's. Records, especially from the 1600s and early 1700s, often simply do not exist or have not yet been found. As discussed earlier, until the early 1800s, Europeans were not in the parts of the island occupied by the Micmacs. Rogers, an early 20th century historian, wrote "while Englishmen were gazing out seawards with their backs turned to the land, Micmacs with their backs turned toward the sea were hurrying to and fro from end to end of the land."*

Because of the closer contact between French and Micmacs at official and cultural levels, and because Cape Breton and the west coast were French territories until 1763 and 1904 respectively, French documentation of Micmacs in western Newfoundland is greater than English-language documentation. The small amount of research that has been done has produced a considerable amount of new documentation. It is clear that any comprehensive statements about the Micmacs of the west coast can be made only after more study of French sources. Written records provide the basis of our understanding of history, and our legitimisation of it. If Europeans did not encounter Micmacs, or considered them unimportant, then written records about Micmacs would not exist. And if we have not searched all archival collections, then we do not know if relevant records are there. Does this absence of known documentation mean that Micmacs did not exist, or that our present "historical record" is an incomplete reflection of an earlier reality?

If we look at history as a collection of information gained through accidental contacts and memories, we must remember that, however valuable it is, it gives only an uneven and incomplete picture. We hope that the contacts and memories in this book will aid Micmac people of western Newfoundland in discovering new parts of the picture of themselves.

' 1911 J.D. Rogers, A Historical Geography of the British Colonies, vol. 5, part 4 Newfoundland. Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 162.

Copyright © 2002-2003 Jasen Benwah

Thanks for Dropping By